2022 Survey of Genomic, Genetic, and Breeding (GGB) Database Team Members

In partnership with Michael Coe (Washington State University)

In Year 1 of our NSF RCN grant (Award Abstract # 2126334), the AgBioData Consortium, in partnership with Washington State University, surveyed database professionals on standardized data curation principles and their implementation in data repositories for agricultural research and breeding programs. We will run a similar survey again at the end of the RCN funding period to assess whether changes in the perception or understanding of FAIR data in our community have occurred.

Summary of Baseline Survey Data

In total, we received 25 usable survey responses, which are summarized below. The full survey report is available here.

1. Survey Sample, Participant Characteristics, and Familiarity and Experience with GGB Databases

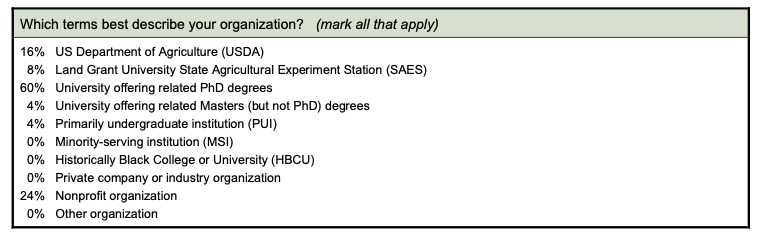

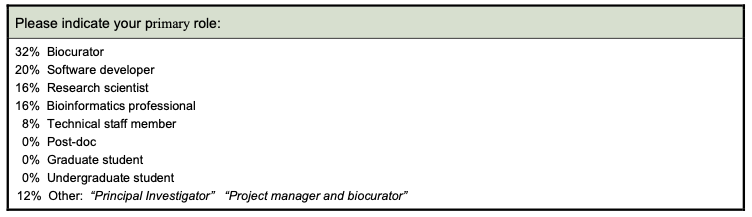

Over half of the respondents (84%) reported working in a university that offers related Ph.D. degrees, in a Land Grant University State Agricultural Experiment Station and the USDA (Table 1). As displayed in Table 2, most reported their primary professional role as being a biocurator (32%), software developer (20%), research scientist (16%), bioinformatics professional (16%), or technical staff member(8%).

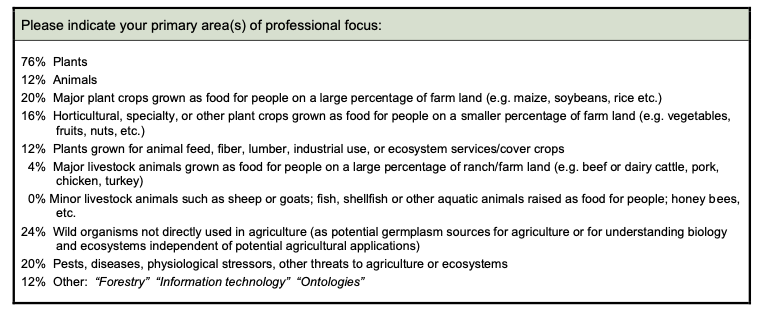

Most respondents (76%) reported a professional focus on plants, including major plant crops (20%), horticultural specialty crops (16%), and plants grown for other purposes besides human consumption (12%; Table 3). Animals were a primary focus for 12% of respondents. Pests, diseases, physiological stressors, and other threats were a focus for 20% of the respondents; 24% reported working on understanding wild organisms not directly used in agriculture.

Table 1. Organizational Affiliations of Survey Respondents

Table 2. Primary Professional Role of Survey Respondents

Table 3. Professional Focus of Survey Respondents

As displayed in Table 4, more than 75% of participants “strongly” or “moderately” agreed that they are very familiar with the concept of FAIR data and could explain this to others (84%) and similarly familiar with FAIR data management practices (76%), and how to make data accessible to researchers (76%). More than 50% gave similar ratings to their familiarity with how to make data reusable (72%), how to make data easily findable (60%), and how to make data interoperable (60%).

Table 4. Team Member Familiarity with Implementation of FAIR Data Practices

2. Baseline Ratings and Recommendations On Implementing FAIR Data Practices in GGB Databases

GGB database team members were asked to rate their level of agreement with a series of statements about their experiences, observations, and opinions regarding the current status of FAIR data practices in GGB databases. They were also asked to rate their priorities for the future development of FAIR data practices in these databases and to provide related comments and written recommendations. There were 16 questions in total, and the responses are summarized below:

- Baseline perceptions of the extent to which the GGB databases provide good guidelines for users on some key FAIR data practices (questions C1-C3):

The highest ratings were given to guidelines related to file formats for preparing and submitting data (89.5%, on average, agreed with the statements), while the lowest ratings were given to guidelines on how to provide information about how the data have been generated and cleaned, how missing data has been handled, and other process transparency issues (75%, on average, agreed with the statement). - About 92% of the respondents slightly, moderately, and strongly agreed that the GGB databases they work for employ cost-sharing efficiencies such as reusable open-source software.

- About 84% of the survey participants think that the GGB databases they work for are presently well curated.

- 76% of the respondents agreed that the GGB databases they work for highlight the importance of the FAIR principles and provide educational resources on this topic

- On average, 78.6% of the respondents slightly, moderately, or strongly agreed that the GGB databases they work for include thorough documentation of how the data have been generated and cleaned and other transparency issues and use metadata and common file formats to facilitate data sharing and integration with other resources.

- Over 80% of the participants agreed that the tools and processes for submitting, finding, and retrieving data from the databases they work for are easy to use and facilitate accurate, efficient transfer of all needed data and metadata according to the FAIR principles.

- 48% of the respondents agreed that reliable interoperability between related databases makes it easy to combine and integrate data in new ways to address new questions, and attempts to find and combine related data on organisms of interest are rarely blocked by technical difficulties.

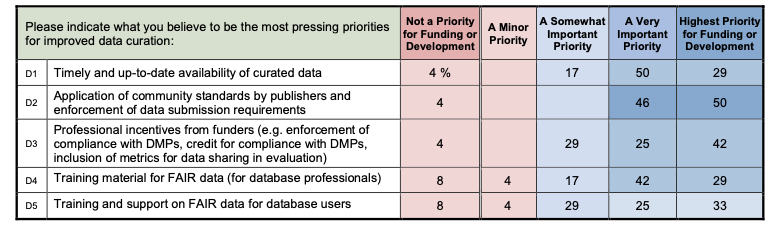

Survey participants were asked to rate the importance of five potential priorities for improved data curation; their responses are summarized in Table 5. All five were rated as being “very important” or “highest priority” by more than half of the respondents.

The highest ratings were given to the application of community standards by publishers and enforcement of data submission requirements,” which was rated as “highest priority” by 50% of respondents and as “a very important priority” by another 46% of respondents. Most of the other priorities were rated as being “very important” or “highest priority” by more than two-thirds of respondents. Training and support on FAIR data for database users received the lowest priority ratings from these team members, with 58% rating this topic as being “very important” or “highest priority.”

Table 5. Baseline Priorities for Further Development of FAIR Data Practices in GGB Databases

3. Recommendations for Topics and Formats of Training Opportunities for Users of GGB Databases

Survey participants were asked an open-ended question “What sort of training opportunities/formats or content/topics for users of these databases would be most helpful?”. Most of the comments can be summarized in the following categories:

- Synchronous (live) educational events online (e.g., webinars) or asynchronous online video presentations, demonstrations, or tutorials. After being recorded, events like webinars can be cut into segments and made into brief asynchronous, "static" video recordings. It is often helpful to design and organize webinars or similar online presentations with this segmentation and re-use in mind (6 comments).

- Static online educational materials, such as tutorials or manuals (5 comments).

- In-person workshops, standalone, or in conjunction with conferences and meetings (1 comment).

- Regular updates of any static online tutorials, manuals, or similar materials so that they reflect the current status of the databases they reference (1 comment).